Hello everyone,

This is Andy, a tea enthusiast.

Have you ever noticed that although tea leaves are normally dark green,

some of them appear noticeably yellow?

Why does this happen?

To explain this phenomenon clearly,

this article will be a bit longer than usual. Thank you for your patience.

Why Do Tea Leaves Turn Yellow?

Tea leaves appear dark green because the chlorophyll molecule contains a magnesium ion (Mg²⁺) at its center.

When chlorophyll undergoes demetalation (loss of magnesium) or when its synthesis or stability is disrupted,

the color gradually shifts from dark green to yellow-green, olive green, and even brownish green.

What Is Chlorophyll?

Chlorophyll has a large structure called a porphyrin ring,

which looks like a spider web.

At the center of this ring sits a magnesium ion (Mg²⁺), firmly held in place.

Chlorophyll has two key features:

1. Large porphyrin ring → absorbs light

2. Central metal ion Mg²⁺ → gives chlorophyll its green color and stabilizes light absorption

If the central magnesium ion is replaced (for example, by hydrogen ions H⁺),

chlorophyll changes from bright green to yellow-green.

This process is known as demetalation.

Interestingly, the structure of chlorophyll is extremely similar to heme,

the oxygen-carrying molecule in human blood.

Similarities:

- Both contain a large porphyrin ring (spider-web-like structure)

- Both play essential roles in energy and life processes

The main difference lies in the central metal:

- Chlorophyll → Magnesium (Mg²⁺)

- Heme → Iron (Fe²⁺)

In other words,

if magnesium in chlorophyll were replaced by iron,

its structure would become very close to that of heme.

“The energy core of green plants and the energy core of human blood share a common ancestor.”

What Causes Yellowing in Tea Leaves?

Yellowing can occur due to demetalation, chlorophyll degradation, insufficient chlorophyll synthesis,

genetic mutations, or physiological damage from cold weather.

Major causes include: acidification, aging, photo-oxidative stress, nutrient deficiency, high-temperature processing, mutations, and cold injury.

① Acidification

When the cellular environment drops below pH 5,

H⁺ ions replace the Mg²⁺ in chlorophyll,

turning it into pheophytin, which appears yellow-green or dark green.

Common scenarios:

- Leaf injury

- Pathogen infection

- Low oxygen within tissues

- Water-logging

- Excessively long withering

- Acidification of fresh tea leaves

This is the most typical and easiest mechanism by which chlorophyll loses its magnesium.

② Aging (Senescence)

As leaves age, photosynthesis weakens, and chlorophyll-binding proteins begin to break down.

At the same time, enzymes such as chlorophyllase and Mg-dechelatase become more active,

accelerating demetalation or chlorophyll degradation, causing the leaf to turn yellow.

This is the main reason behind autumn foliage and yellowing of older tea leaves.

③ Photo-oxidative Stress

Under strong sunlight, high temperatures, or drought,

tea leaves produce a large amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

ROS attack chlorophyll and photosystems, causing chlorophyll degradation or demetalation.

Common scenarios:

- Intense direct sunlight

- Sudden removal of shade

- Heat waves

- Dry hot winds

- Water deficiency

The leaves may show pale yellow-green or mottled yellow patterns—

a common form of light damage in summer tea gardens.

④ Magnesium Deficiency

Magnesium is the central element of chlorophyll and is a mobile nutrient.

When Mg is lacking, plants cannot synthesize sufficient chlorophyll in new leaves.

Older leaves show the classic pattern of green veins with yellow interveinal areas.

Although this is not demetalation,

the result is still a yellow-green appearance.

⑤ Heat-Induced Changes (Processing Effects)

At temperatures above 70–80°C, chlorophyll becomes unstable.

If moist leaves become acidic during heating, demetalation can occur rapidly,

turning the leaves olive green or dark yellow-green.

Common in tea processing:

- Delayed kill-green, fixing, pan firing (sha-qing)

- Acidification during withering

- Exposure to steam

- Over-moist leaf material during heating

This is the origin of “men-huang” (steamed-yellow)”.

⑥ Enzymatic Degradation

When leaves are damaged, aged, or infected,

enzymes such as chlorophyllase and Mg-dechelatase become active,

removing chlorophyll side chains or directly causing demetalation,

leading to pale yellow-green coloration.

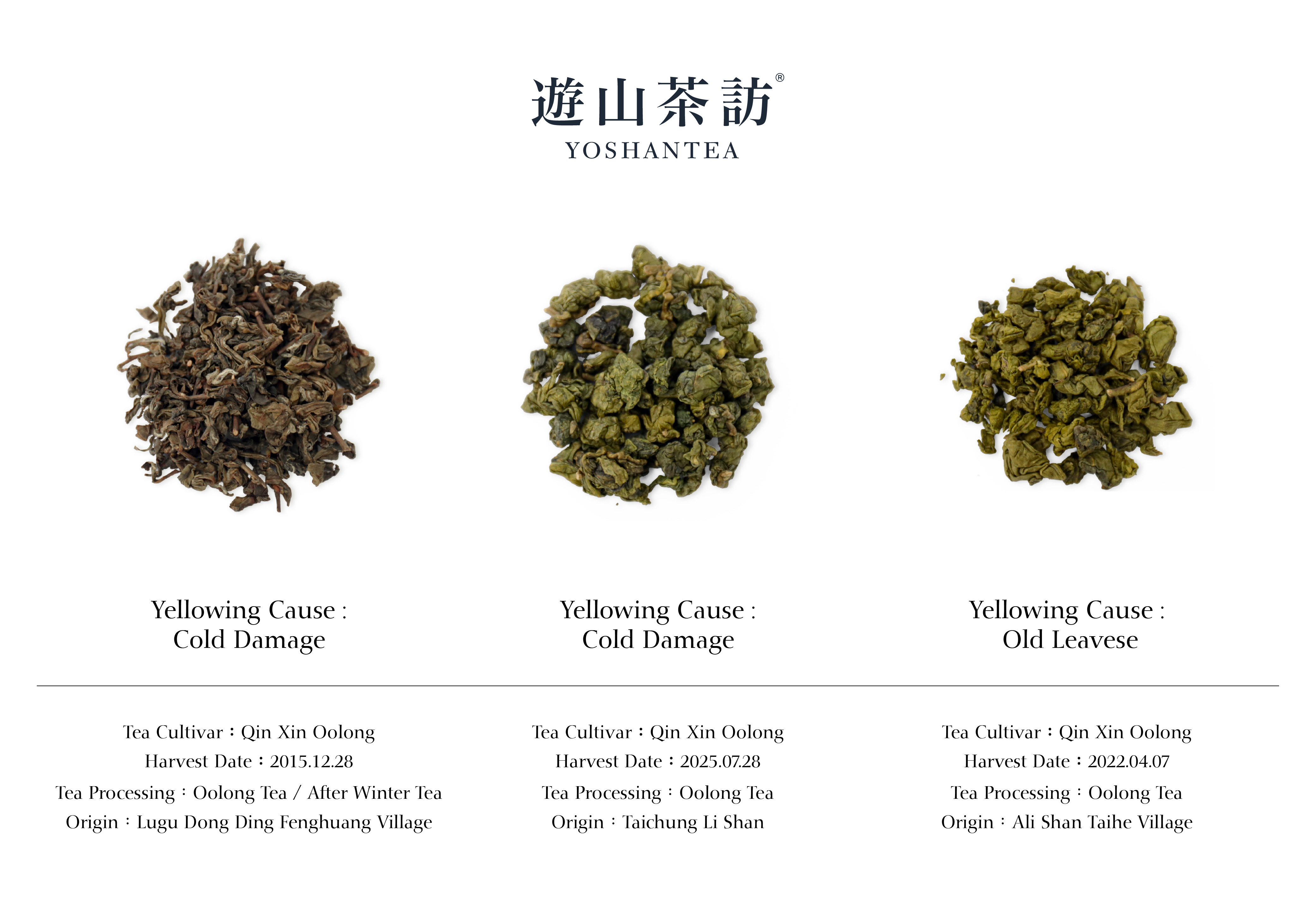

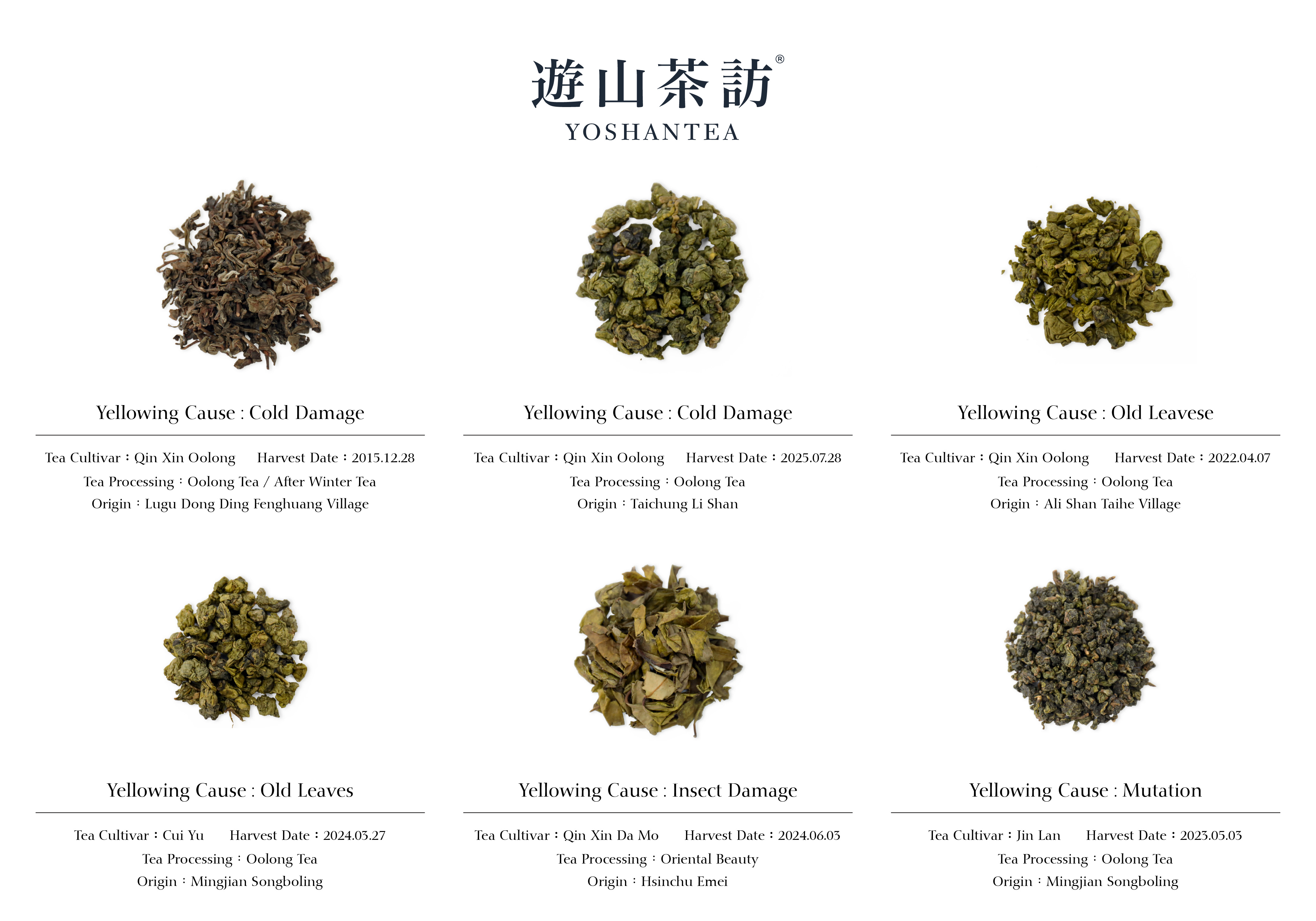

⑦ Cold-Induced Yellowing and Demetalation

Cold stress affects chlorophyll through multiple mechanisms:

light inhibition, metabolic slowdown, and cell damage.

Tea is a subtropical plant and is especially sensitive to low temperatures,

so yellowing is common in winter and during cold waves.

Frequently seen in Ali Shan tea, high-mountain tea, and winter-harvest teas (late winter teas).

Major mechanisms include:

A. Low temperature halts photosynthesis → ROS accumulation

Low temperatures reduce the activity of photosynthetic enzymes.

Light energy that cannot be processed turns into ROS,

which attack chlorophyll and induce demetalation or breakdown.

Symptoms:

- Pale yellow-green

- Mottled yellow patterns

- Sun-burn-like lesions

This is the most common yellowing mechanism during long cold periods.

B. Low temperature suppresses chlorophyll synthesis

Key enzymes such as Mg-chelatase and POR lose activity under low temperatures,

preventing young leaves from forming chlorophyll properly.

Resulting symptoms:

- Yellowish or pale green new leaves

- Light sensitivity

This resembles insufficient synthesis, not demetalation.

C. Cold injury → membrane damage → acidification → demetalation

Near 0°C or frost events, membranes rupture,

allowing acidic vacuolar contents to leak out and lower local pH,

directly promoting demetalation.

Leaves become deeper yellow-green, olive-green, or dark yellow-green,

often with scorched edges.

D. Actual effects seen in tea gardens after cold waves

- New buds: insufficient synthesis → pale yellow-green

- Mature leaves: ROS accumulation → mottled yellowing

- Frost-damaged leaves: acidification + demetalation → olive green, dark yellow-green, scorched edges

These conditions reduce photosynthetic efficiency and affect spring-tea quality,

forming part of the characteristic flavor of winter-piece tea.

⑧ Mutations Causing Yellowing or Whitening

In some plants, yellowing is not caused by environmental factors

but by genetic mutations that affect chlorophyll synthesis, binding, or degradation.

These mutation-induced yellowing types can be grouped into three categories:

A. Mutations in chlorophyll biosynthesis genes

If enzymes such as Mg-chelatase, POR, or CAO are mutated,

chlorophyll cannot be synthesized properly,

and new shoots appear pale yellow or yellow-white.

This type of yellowing is stable, long-lasting, and does not improve even if the environment does.

Some yellow-shoot tea varieties fall under this category.

B. Mutations affecting chlorophyll-binding proteins or the photosystem

When genes related to the light-harvesting complex (LHC) or photosystems mutate,

chlorophyll can be synthesized but cannot be stably incorporated into the photosystem.

To avoid light damage, plants actively degrade chlorophyll.

Leaves appear pale yellow-green or show variegated patterns.

C. Mutations that accelerate chlorophyll degradation or demetalation

If enzymes such as chlorophyllase or Mg-dechelatase are overactive due to mutation,

chlorophyll is rapidly degraded or demetalated,

leading to fast and uniform yellowing similar to aging.

Mutation Yellowing in Tea Plants

Tea plants with yellow, white, or golden shoots often show:

- Higher amino acid content

- Lower polyphenol content

- Sweeter, umami-rich flavor

The cultivar “Jin Lan”, derived from a mutation of Four Seasons Spring (Si Ji Chun),

is one well-known example.

These yellowing types result from insufficient chlorophyll synthesis,

not from demetalation, and therefore appear pale yellow or golden rather than dark yellow-green.

Summary: Four Major Causes of Yellowing in Tea Leaves

1. True Chlorophyll Demetalation

- Acidification (leaf injury)

- Enzymatic demetalation (leaf injury)

- High temperature or heat damage (over-frying, steaming stagnation)

- Cold injury causing cellular acidification (high-mountain tea, winter tea, winter-piece tea)

2. Chlorophyll Degradation

- Aging (overmature leaves)

- Photo-oxidative stress

- ROS attack

3. Insufficient Chlorophyll Synthesis

- Magnesium deficiency (nutrient shortage)

- Low-temperature inhibition of chlorophyll synthesis (high-mountain tea, winter tea, winter-piece tea)

4. Mutations in the Photosystem or Chloroplast

- Defective light-harvesting proteins

- Incomplete chloroplast development

- Variegated mutations

Color-Based Summary

- Demetalation → dark yellow-green, olive green

- Insufficient synthesis → pale yellow, light green, golden yellow

- Light damage → mottled yellowing

- Mutations → uniform and stable yellowing or variegation

-Additional Knowledge: Why Matcha Foods Should Not Be Heated

Matcha’s vivid green color comes from natural chlorophyll.

However, natural chlorophyll is very sensitive to heat, acid, and light.

When matcha is heated to 70°C or higher, three things occur:

1. Chlorophyll begins to break down

2. Heat accelerates demetalation, producing dark yellow-green pheophytin

3. Polyphenol oxidation further darkens the color to yellow or brown

Therefore, heated matcha products typically shift from

bright green → yellow-green → dark green → brownish green.

This is why baked matcha pastries often lose their vibrant green color.

If a "matcha" product retains a bright, fluorescent green even after heating,

one should be cautious—

it is likely not natural matcha.

Possible coloring agents include:

- Copper chlorophyllin

- Sodium copper chlorophyllin

These are artificially stabilized pigments in which the natural Mg²⁺ is replaced with Cu²⁺,

making the pigment resistant to heat, acidity, and light.

The more heat-resistant the "matcha green" looks,

the more likely it contains copper chlorophyll derivatives.

Regulations and Safety Concerns

Copper chlorophylls are legal additives in some countries (including Taiwan),

but only within defined limits and approved food categories.

Safety concerns arise mainly from:

1. Overuse

2. Use in prohibited food products

According to Taiwan’s "Standards for Food Additives":

Copper chlorophyllin may be added to:

1. Chewing gum, bubble gum (≤ 40 mg/kg as copper)

2. Capsule or tablet-type foods (≤ 500 mg/kg)

Sodium copper chlorophyllin may be added to:

1. Chewing gum, bubble gum (≤ 50 mg/kg as copper)

2. Capsule or tablet-type foods (≤ 500 mg/kg)

3. Dried kelp (≤ 150 mg/kg as copper)

4. Preserved vegetables/fruits, baked goods, jams and jellies (≤ 100 mg/kg)

5. Flavored milk, soups, non-alcoholic flavored beverages (≤ 64 mg/kg)

JECFA reports that copper chlorophyll complexes showed no chronic toxicity

in long-term rat studies.

WHO suggests an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 15 mg per kg body weight,

meaning a 60 kg adult may safely consume up to 900 mg per day.

Products containing these colorants outside of permitted categories are illegal.

I hope this information is helpful.

Next time you brew tea, try removing the particularly yellow leaves.

In my experience, such leaves often taste lighter but not bitter;

they have a gentle, unique flavor.

See you next time.

#yoshantea #taiwantea #dongdingtea #oolongtea #teafacotry #FSSC22000 #safetea #chlorophyll #demetalation #pheophytin #wintertea #winterflushtea #highmountaintea #matcha #foodscience #teaoxidation #teaprocessing